This is sort of a follow-up to a

recent

post,

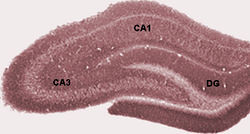

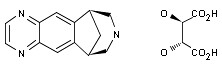

in which I discussed the correlation between administration of

fluoxetine, and neurogenesis in the hippocampus. In that

post, I

mentioned that skeptics of psychopharmacology are fond of pointing out

the lack of a well-defined connection between the inhibition of

serotonin reuptake, and the clinical effects of the serotonin reuptake

inhibitors.

The hypothesis that there is a connection between serotonin and

depression is a refinement of the monoamine hypothesis of depression.

That hypothesis states that there may be a connection between

relative underactivity of brain monoamines (serotonin, norepinepherine,

dopamine) and depression. It is an old idea, derived in part

from studies such as this one: Antagonism to reserpine

induced depression by imipramine, related psychoactive drugs, and some

autonomic agents

. Sigg EB, Gyermek L, Hill

RT.

Psychopharmacologia. 1965 Feb

15;7(2):144-9.

Obviously, we have learned a lot since 1965, so the monoamine

hypothesis is significant mainly as an historical relic. Even

the refinement -- the serotonin hypothesis -- is ancient.

Since then, ample evidence has been found, showing that the

serotonin hypothesis is, at best, a gross oversimplification.

There is no strict correlation between serotonin activity and

any defined mental illness.

The lack of a strict correlation means that the action of

antidepressant

medication is not fully understood; nobody I know will dispute that.

But the thing is, harping on that string is pointless. It is

like

pointing out that there is not a strict correlation between the noise

of an automobile engine, and the motion of he automobile. It

is

true that sometimes an automobile moves without the engine making

noise; and sometimes the engine makes noise without moving.

Sometimes there is a significant lag between the time the

engine

starts making noise, and the time the automobile starts to move.

With the correct instruments, it would even be possible to

show

that

none of the energy that goes into the production of noise has anything

to do with the movement of the automobile. True, all of it.

But can we conclude that there is no connection between the

noise

of the automobile, and the motion?

Perhaps the serotonin boost is not at all related to the clinical

effect. It could be an

epiphenomenon.

Physicians generally know about epiphenomena, and are

cautious about overinterpreting them. Pointing out the fact,

that there is not necessarily a causal connection, is tiresome.

Thus, when a skeptic takes pains to point it out, it merely

shows that the skeptic is not aware of how obvious it is to

medically-educated people.

As an aside, it occurs to me that epiphenomena are roughly analogous to

spandrels.

If I felt like getting tediously philosophical, I could write

a post outlining that analogy. Another time, perhaps.

(A hint: just as a feature that evolves as a spandrel can

turn out to be useful, sometimes side effects of mediation can be

useful.)

Sometimes it is difficult to avoid getting tediously philosophical.

Oh well. It occurs to me also that this is an

example of how a good understanding of evolutionary theory can be

helpful in understanding medicine, as Orac is

fond

of pointing out. (As is my former residency

director,

Randy

Nesse.) This is true regardless of whether you

believe that evolution is responsible for the origin of species.

Putting that aside aside, and getting back to the point: Because it is

tiresome to hear skeptics harp on that string (the lack of a

fully-delineated connection between serotonin and depression) I was

surprised to see this article in a well-regarded journal:

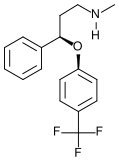

Serotonin

and Depression: A Disconnect between the Advertisements and the

Scientific Literature, by Jeffrey R. Lacasse and

Jonathan Leo.

Illustration:

Margaret Shear, Public Library of Science

I was surprised to see this, because it is, to me, a new twist on the

old theme. The authors do not imply that antidepressant

medication does not work; nor do they argue that psychopharmacology is

suspect.

To equate the impressive recent achievements of

neuroscience with support for the serotonin hypothesis is a mistake.

Rather, they argue that it is inappropriate for pharmaceutical

companies to base advertising campaigns upon the presumed link between

serotonin and depression.

In the US, the FDA monitors and regulates DTCA.

The FDA requires that advertisements “cannot be false or

misleading” and “must present information that is

not inconsistent with the product label” [27]. Pharmaceutical

companies that disseminate advertising incompatible with these

requirements can receive warning letters and can be sanctioned. The

Irish equivalent of the FDA, the Irish Medical Board, recently banned

GlaxoSmithKline from claiming that paroxetine corrects a chemical

imbalance even in their patient information leaflets [29]. Should the

FDA take similar action against consumer advertisements of SSRIs?

Curiously, the authors devote several paragraphs to debunking the

serotonin hypothesis, even though, in my opinion, their purpose could

have been served with one or two citations. What is even more

curious is that they do not go on to draw a specific conclusion that

answers the question they pose: they never answer directly the question

about whether the FDA should take action against the pharmaceutical

companies that refer to the serotonin hypothesis in their

advertisements.

In fact, they do make a good case against the pharmaceutical companies,

and I happen to agree. It appears to be true, based upon

their argument, that pharmaceutical companies are not following FDA

regulations regarding DTC advertisements. Moreover, the

authors make several other good points, such as this one:

Patients who are convinced they are suffering from a

neurotransmitter

defect are likely to request a prescription for antidepressants, and

may be skeptical of physicians who suggest other interventions, such as

cognitive-behavioral therapy [48],

evidence-based or not.

I personally have spent a lot of time in the office, with patients,

trying to undo the misinformation contained in DTCA. It

bothers me that I have to do that. I would much rather spend

the time providing good education, not undoing bad education.

I would prefer to not have to deal with direct-to-consumer

advertising at all; but if we have to have it, companies really ought

to be held to the standards that exist to ensure balance and accuracy.

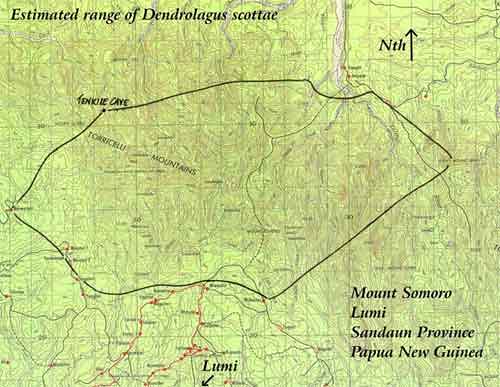

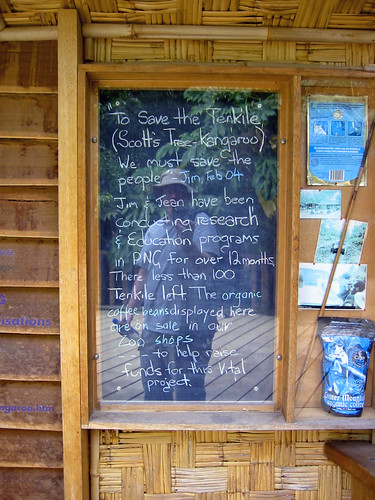

What is

interesting about the TCA's effort is the way they are helping to

reduce predation of tenkiles. The local humans traditionally

have hunted the tenkile. The TCA has

What is

interesting about the TCA's effort is the way they are helping to

reduce predation of tenkiles. The local humans traditionally

have hunted the tenkile. The TCA has

:

Joseph j7uy5

:

Joseph j7uy5