A recent version of the NYT carried this article. (It's a

blogsafe link, so it should still work even after the article goes into

the archive.)

Who's Mentally Ill? Deciding Is Often All in the Mind

By BENEDICT CAREY

Published: June 12, 2005

THE release last week of a government-sponsored survey, the most

comprehensive to date, suggests that more than half of Americans will

develop a mental disorder in their lives.

The study was the third, beginning in 1984, to suggest a significant

increase in mental illness since the middle of the 20th century, when

estimates of lifetime prevalence ranged closer 20 or 30 percent. [...]

That evolving understanding can have implications for diagnoses. For

example, in 1973, the American Psychiatric Association dropped

homosexuality from its manual of mental disorders, amid a growing

realization that no evidence linked homosexuality to any mental

impairment. Overnight, an estimated four to five million "sick" people

became well.

More common, however, is for psychiatrists to add conditions and

syndromes: The association's first diagnostic manual, published in

1952, included some 60 disorders, while the current edition now has

about 300, including everything from sexual arousal disorders to

kleptomania to hyposomnia (oversleeping) and several shades of bipolar

disorder.

"The idea has been not to expand the number of people with mental

conditions but to develop a more fine-grained understanding of those

who do," said Dr. Ronald Kessler, a professor of health care policy at

Harvard Medical School and lead author of the latest mental health

survey.

Naturally, I was curious about this, so I looked up the study,

meanwhile feeling irritated by the lack of a direct reference to the

study. I know the NYT thinks hyperlinks are beneath their

dignity, but even a printed reference would be nice. Anyway,

this appears to be the study:

Prevalence and Treatment of Mental Disorders, 1990 to 2003

Ronald C. Kessler, Ph.D., et. al.

NEJM Volume 352:2515-2523

[...] Results

The prevalence of mental disorders did not change during the decade

(29.4 percent between 1990 and 1992 and 30.5 percent between 2001 and

2003, P=0.52) [...]

In the NYT article's second paragraph, the author stated "The study was

the third, beginning in 1984, to suggest a significant increase in

mental illness..." Yet the first sentence in the

Results

section of the abstract states no such thing. In fact, the

study shows that the small increase from 1990-2 to 2001-3 is as likely

as not (P=0.52) to be a mere artifact of the study design or

implementation. The study is not about any possible

change in lifetime incidence from the middle of the 20th century to the present

time.

The aim of our study

was to present more comprehensive data on national trends with regard

to the prevalence and rate of treatment of 12-month mental disorders

based on the NCS, conducted from 1990 to 1992, and the NCS Replication

(NCS-R), conducted from 2001 to 2003.

One potential point of confusion is that the NYT author, Mr. Carey, emphasizes discussion of

lifetime prevalence, which is a different statistic than the

12-month prevalence

numbers emphasized in the NEJM article. That is not

necessarily a problem, although it would have been good for him to take

a moment to clarify the point. Even allowing for that, the

guy made a mistake. Earlier studies may have indicated a

lifetime prevalence of 20-30%, but the NEJM study does not address that.

The mistake, however, actually is not what this

post is about, although I do take pains to point it out.

Rather, if you read the NYT article, then read the original

study, you would not have any idea that the former had anything to do

with the latter. So what, exactly, is the article about?

It appears that Mr. Carey used the occasion of the publication of the

NEMJ article to blather on about his own ideas about mental health

diagnosis and treatment. Snarky readers, no doubt, realize

that what Carey did is exactly what I often do in this blog, so who am

I to be critical?

Good question. The answer is that this is a

blog, but the New York Times is a

newspaper.

If someone is going to write an article that starts out with:

"THE release last week of a government-sponsored survey, the most

comprehensive to date, suggests that more than half of Americans will

develop a mental disorder in their lives...", then it seems that the

article should be about the study.

If the author wants to take the opportunity to express his varied

opinions, and connect all kinds of things that are not directly

connected, fine. Just do it on the op-ed page; or better yet,

get a blog and do it there.

Although I disagree with a lot of what he says, it still is an

interesting article, and is worth reading. It would make a

great blog post. The problem is that, if the reader is not

careful, it would be possible for the reader to get the impression that

the opinions expressed by the author are backed up by the scientific

article he has cited, or at least by some of the scientists he quotes.

To be fair, Carey does not make any declarative statements of opinion; rather, he implies them, as in this section:

But what does it mean

when more than half of a society may suffer "mental illness"? Is it an

indictment of modern life or a sign of greater willingness to deal

openly with a once-taboo subject? Or is it another example of the

American mania to give every problem a name, a set of symptoms and a

treatment - a trend, medical historians say, accentuated by drug

marketing to doctors and patients?

The NEJM article says

nothing about drug marketing. None of

the other experts, of those quoted in the article, are quoted as having

said anything about drug marketing. Carey does not cite,

specifically, any studies about drug marketing. (There have

been such studies, but none is cited.) I agree with the

implication, that drug marketing is an interesting topic; I've

probably posted on that subject at least a dozen times, and cited

studies, but he offers this question, with no attempt to answer it.

Is it true that drug marketing accentuates the American mania to give

every problem a name? Is it even true that it is an

American

mania, or even a mania at all? If so, what name should we

give to a mania about giving things a name? (

Diagnosomania, American

type, severe, with obsessive features?)

Note that I do not mean to impugn the entire newspaper, nor do I intend

to imply that any of Mr. Carey's other articles are suspect in any way.

I just want to point out that readers need to be careful when

reading these kinds of articles, regardless of who wrote them, or where they are published.

The results of the 2005 Pinto Horse Association World Championship have been posted

The results of the 2005 Pinto Horse Association World Championship have been posted

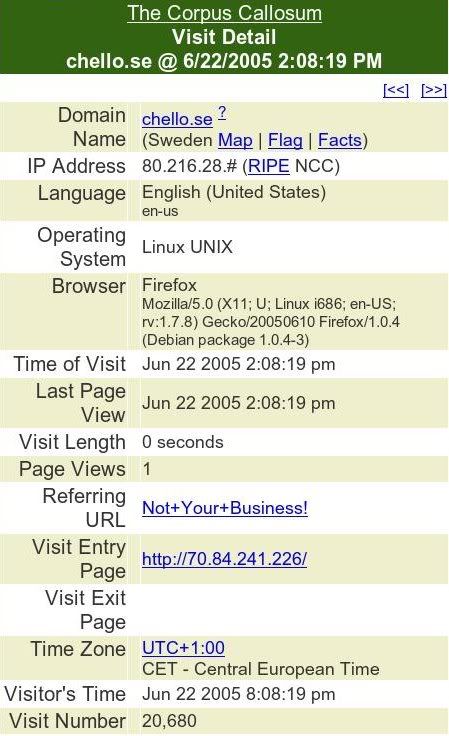

This

visitor chose to obscure the referring URL. I used to do

that, with a statements such as "mind your own business" or "why are

you reading this?"

This

visitor chose to obscure the referring URL. I used to do

that, with a statements such as "mind your own business" or "why are

you reading this?"  To

the right is the modern-day picture of one of the survivors of a napalm

attack in Viet Nam. Her injuries were unintentional;

they resulted from an accidental release of the incendiary chemical en

route to an attack on a military target. The incident

occurred on June 8, 1972. Kim, then 9 years old, was hiding in a

To

the right is the modern-day picture of one of the survivors of a napalm

attack in Viet Nam. Her injuries were unintentional;

they resulted from an accidental release of the incendiary chemical en

route to an attack on a military target. The incident

occurred on June 8, 1972. Kim, then 9 years old, was hiding in a

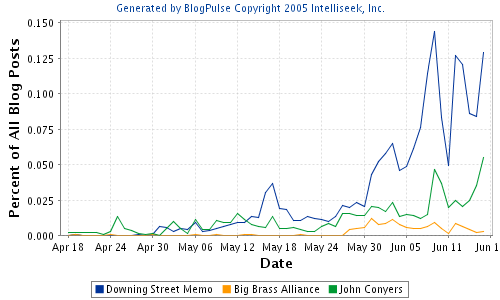

The reason so many people are calling for an investigation is not that

the DSM is conclusive; if that were the case, no investigation would be

needed. Rather, the reason people are getting all worked up

is that there are many, many little bits of information, many little

dots from which an image can be discerned. And the picture

that is emerging is not one of those pointillistic riverfront scenes;

rather, it is a scene like the destruction of the USS Maine in Havana

Harbor. The DSM has become the rallying point, like the Alamo, or Pearl Harbor.

The reason so many people are calling for an investigation is not that

the DSM is conclusive; if that were the case, no investigation would be

needed. Rather, the reason people are getting all worked up

is that there are many, many little bits of information, many little

dots from which an image can be discerned. And the picture

that is emerging is not one of those pointillistic riverfront scenes;

rather, it is a scene like the destruction of the USS Maine in Havana

Harbor. The DSM has become the rallying point, like the Alamo, or Pearl Harbor.

Everyone's favorite Condoleezza,

Everyone's favorite Condoleezza,

:

Joseph j7uy5

:

Joseph j7uy5